Food prices in Greece show an explosive increase, recording a 30% rise since 2019 according to a recent report by Eurostat. This dramatic escalation in the cost of basic goods particularly hits Greek households, creating serious challenges in citizens’ daily living, as reported by Powergame.gr.

Read: The “myth” of Sklavenitis about stopping food price reductions, profit transfers and real estate

Comparison of Greek food prices with European countries

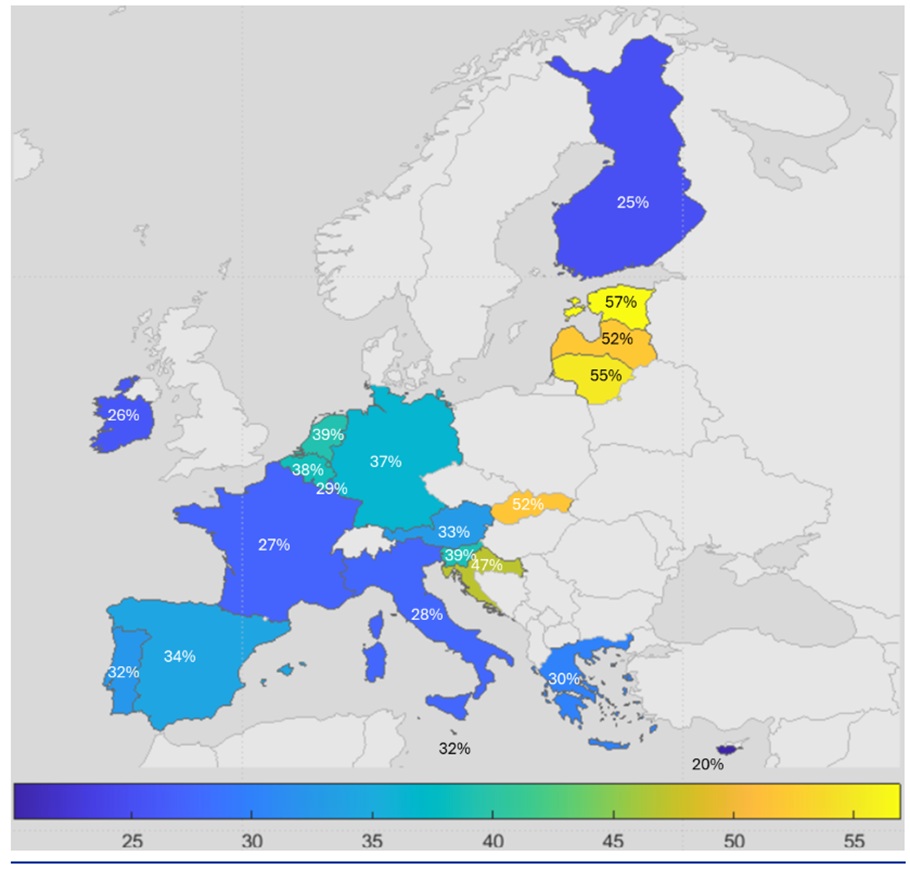

Eurostat’s analysis reveals that food prices in Greece, while high, are not a unique phenomenon in Europe. Baltic countries and Slovakia record an impressive jump of 50%, while Germany shows an increase of 37%. In France the percentage stands at 27%, in Italy at 28%, while in Spain it reaches 34%. The Netherlands records increases of 38-39%. The critical issue that differentiates the Greek reality is the limited purchasing power of consumers and the wage gap, factors that make these increases unbearable for Greek households.

Impact on low incomes and social inequalities

Eurostat’s report emphasizes that food prices disproportionately burden low incomes. Basic food goods constitute an integral part of the family budget, leaving minimal room for maneuver for economically vulnerable categories. According to the data, one in three consumers worries about their ability to purchase desired foods. Prices remain one-third higher compared to the pre-pandemic period, creating a sense of poverty among consumers during their visits to supermarkets.

Inflation and monetary policy in the Eurozone

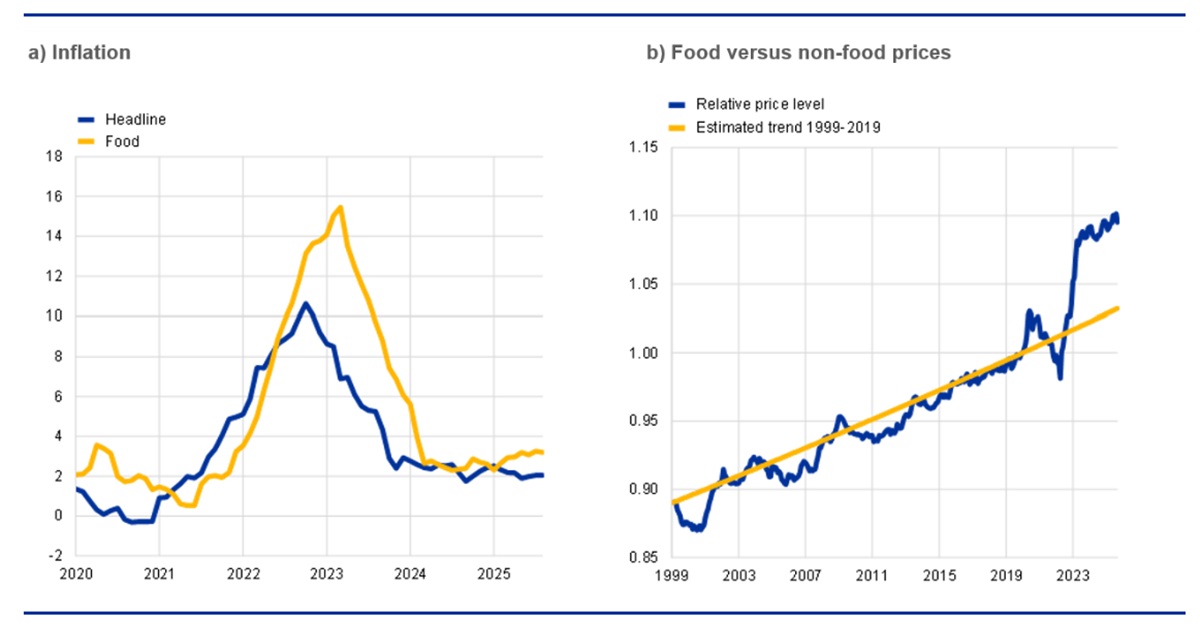

In August, inflation in Greece was finalized at 3.1%, significantly exceeding the Eurozone average which stands at 2%. This percentage corresponds to the European Central Bank’s target for interest rates. A noticeable improvement is observed compared to October 2022, when Eurozone inflation had peaked at 10.6%. Meanwhile, wages increased, partially offsetting previous losses in real income.

Central banks, including the ECB, focus on overall price changes, often overlooking individual components such as energy, services and food. This approach provokes increasing criticism for “fixation on numbers” that doesn’t correspond to the real economy nor improve consumers’ daily lives.

Key conclusions about high food prices

Eurostat reaches three critical conclusions:

• The gap between food prices and overall prices is larger and more persistent than in the past

• Food prices continuously affect everyone and shape inflation expectations

• Price increases hit poorer households more severely

Since the introduction of the euro in 1999, food prices show an upward trend, however the gap since 2022 is extremely persistent, while the discussion about climate change impacts on Europe’s food security intensifies.

Which products show the biggest increases

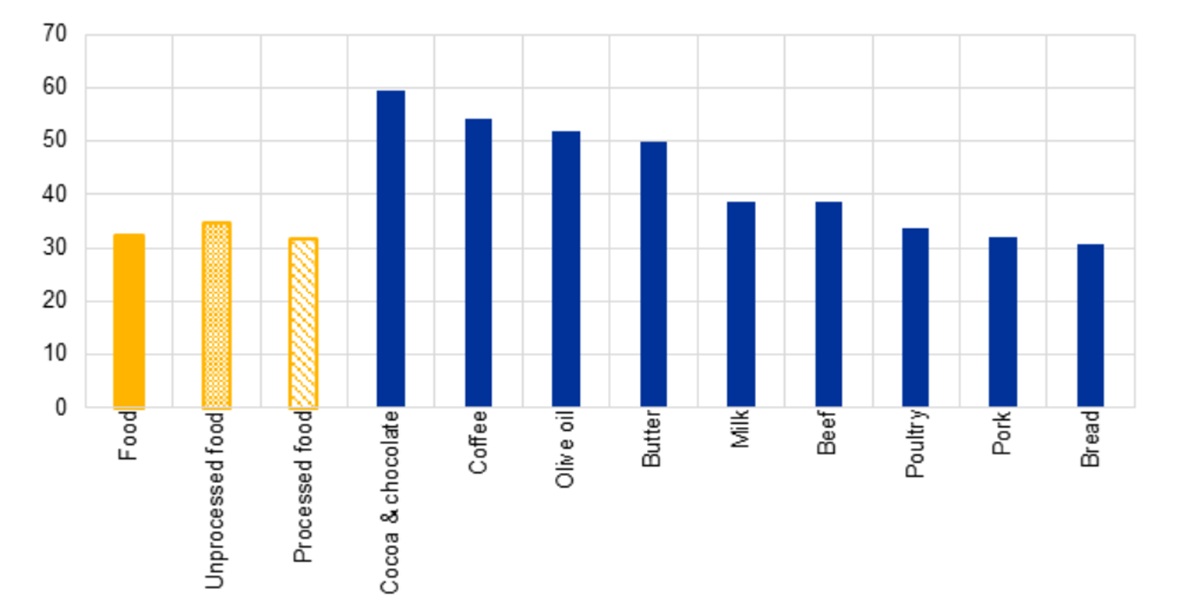

Food price evolution shows heterogeneity between categories and member states. Beef meat, poultry and pork record increases above 30% compared to late 2019. Milk shows a jump of about 40%, while butter reaches 50% compared to pre-pandemic levels. Even more impressive are the increases in coffee, olive oil and chocolate.

Causes of food price explosion

The war in Ukraine constitutes a decisive factor for the food price surge. The Russian invasion on February 24, 2022 overturned supply chains and disrupted the energy system, as Russian oil and natural gas had been feeding Europe for years. Globally, income increases in emerging markets strengthened demand for agricultural products, exerting upward pressure on prices. Meanwhile, productivity increases in agriculture lag behind for various reasons.

Climate change emerges as a critical factor affecting food prices. Extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, become more frequent and seriously disrupt supply chains, drastically reducing production.

A characteristic example is the prolonged droughts in southern Spain in 2022 and 2023, which led to a sharp increase in olive oil prices, with cans reaching 200 euros. Also, coffee and cocoa prices skyrocketed after adverse weather conditions in key exporting countries like Ghana and Ivory Coast, resulting in take-away coffee costing 2.20 to 2.70 euros. Meanwhile, consumers face “hidden increases” through shrinkflation, as high energy costs pressure industries to proceed with new price hikes, reducing product sizes.